April 4, 2025 | Chandler Sanchez, Travis Madsen, Laura Wickham, & Caitlin Gatchalian

In late February 2025, the U.S. House of Representatives adopted an outline for the federal budget, aiming to extend $4.5 trillion worth of tax cuts while cutting at least $1.5 trillion in federal spending over the next 10 years.

Where is all of that money going to come from? Your guess is as good as ours.

However, some ideas under consideration would set America and the Southwest back when it comes to energy efficiency, costing us all more in the long run. For example, repealing federal tax credits that support advanced energy manufacturing and efficient transportation would be counterproductive and harmful. Such a move would undermine jobs that are emerging in key manufacturing centers across the Southwest, and encourage residents and businesses to waste money purchasing inefficient vehicles that burn thousands of unnecessary dollars on fuel.

In this report, we review how federal electric vehicle (EV) tax credits currently work and what impact repealing them would have for businesses and consumers across the Southwest.

*Note: this analysis does not attempt to incorporate the effect of any new federal tariffs that have been contemplated, announced, implemented, or withdrawn. Those tariffs introduce substantial uncertainty. They will have different effects on different brands and on models within brands, and it is unclear how long the policies will be in place or what exemptions may be introduced. For the 25% tariff on imported cars anticipated to go into effect on April 2, analysts are predicting price increases in the $6,000 range for affected models. Vehicles of any propulsion technology assembled in the United States may look more attractive if this policy holds, although manufacturers could face real difficulties accommodating rapid changes in demand, and there could be supply and price disruptions across the board as a result.

Despite this new uncertainty in the overall automotive market, we continue to believe that our analysis here provides a useful base of understanding for the value of the federal EV tax credit. We may update the analysis at a later time to better incorporate tariff effects should they become firmly established.

Federal EV tax credits

When Congress adopted the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022, leaders included almost two dozen advanced energy tax credits, many of which support improvements in energy efficiency across the American economy, as well as encouraging more companies to locate manufacturing operations domestically rather than overseas.

Those tax credits include the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit (45X), which offers an incentive for companies that make batteries or mine critical minerals domestically. There are also a series of credits supporting EV deployment, including a credit for individuals or businesses that purchase a new EV; provisions that make credits claimable by tax-exempt entities including governments and non-profit organizations; provisions that enable customers to claim credits in full at the point of sale; and a credit toward installing EV charging infrastructure in targeted locations. The law also includes a limited credit toward the purchase of used EVs, aimed at expanding the universe of people who can participate.

The individual clean vehicle credit offers up to $7,500 off the purchase or lease of a new passenger EV. Currently only about 16 models qualify under the law’s North American assembly and battery sourcing and manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP) requirements, which Congress enacted to give manufacturers an incentive to create local jobs making relatively affordable EVs. More vehicles could qualify in the future as the domestic supply chain develops and expands.

The commercial clean vehicle credit offers $7,500 for light-duty vehicles and up to $40,000 for medium- and heavy-duty EVs. It does not include the same sourcing requirements as the individual credit. It can also benefit individuals who lease an EV from an auto dealership that has purchased the vehicle and chosen to pass along a discount.

We can already see the impacts that these tax credits are having here in the Southwest in the form of new manufacturing jobs and increasing EV sales.

New manufacturing hubs and new jobs

Advanced energy tax credits have encouraged companies to announce plans to invest $21 billion in mineral extraction, battery manufacturing or recycling, and EV assembly facilities across the six-state U.S. Southwest region, which could create more than 12,000 new good-paying jobs when fully realized. Highlights include:

- Northern Nevada is emerging as a globally significant battery technology hub, with companies and projects covering the full life-cycle of battery projects, many of which support efficient transportation. From Reno to Elko to Humboldt County, Nevada is home to mineral resources like Lithium Americas’ Thacker Pass project; high-tech battery manufacturing operations (such as Lyten, Nanotech Energy, American Battery Technology Company and Octillion Power Systems); and end-of-life battery recycling and re-manufacturing facilities, including Redwood Materials.

- Major battery and vehicle manufacturers are looking to Arizona for its friendly business climate and abundance of qualified workers. For example, LG Energy Solutions is investing $5.5 billion to build a battery factory near Queen Creek which will likely be America’s largest when it opens in 2026. On top of that, American Battery Factory is investing $1.2 billion to build a gigafactory near Tucson that will ultimately deliver as many as 1,000 new local jobs. And Lucid Motors has chosen Casa Grande as its vehicle manufacturing hub.

- In Colorado, Solid Power Inc. is expanding a high-tech battery factory in Thornton, bringing a hundred new construction jobs and 40 ongoing operations jobs. And Amprius Technologies has signed a letter of intent to open a new $190 million battery factory in Brighton this year, to serve contracts ranging from vehicle manufacturers to the military. Both of these companies are commercializing new battery technologies that could bring performance and weight advantages to future generations of EVs.

Increasing EV sales

Advanced energy tax credits are simultaneously lowering the up-front cost to acquire and deploy an energy-efficient EV and making cost-savings on fuel and maintenance more accessible for more residents and businesses across the Southwest. Coupled with improvements to vehicle technology and availability as models diversify and manufacturing scales up, the credits are helping to dramatically accelerate efficient vehicle deployment across the Southwest.

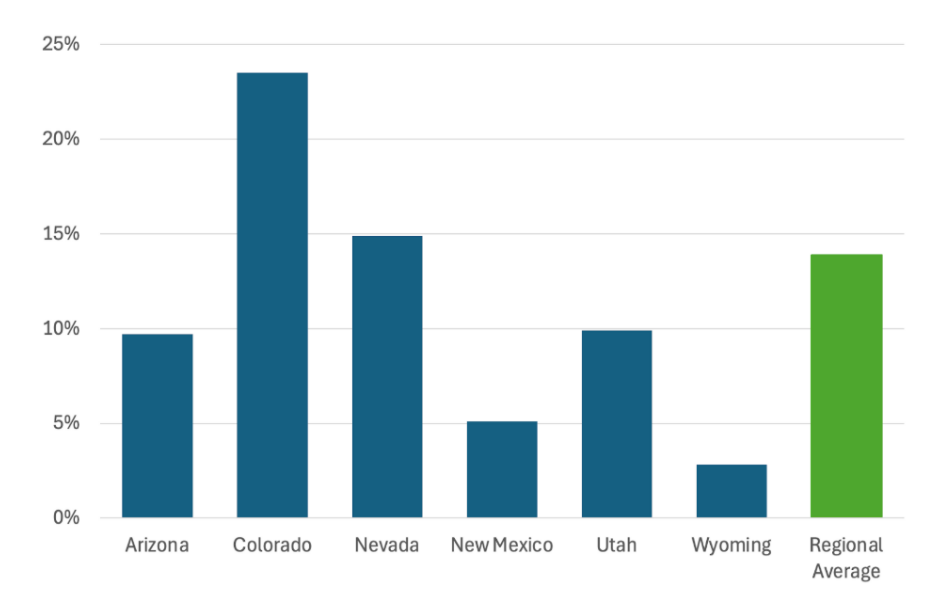

Since the enhanced EV tax credit was enacted into law in 2022, annual light-duty EV sales in the six-state U.S. Southwest region have more than doubled. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: The light-duty EV market in the U.S. Southwest is taking off

Data represents new EV registrations by year in AZ, CO, NV, NM, UT, and WY. Source: Atlas Public Policy

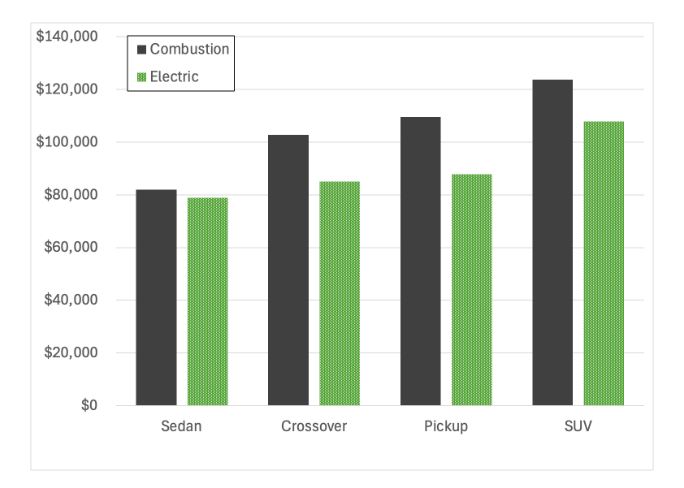

Within the region, Colorado leads the pack, with new EV registrations in 2024 approaching a quarter of the overall light-duty new vehicle market. (See Figure 2.) According to the Colorado Automotive Dealers Association, Colorado finished 2024 with EVs accounting for more than 30% of sales in the final quarter. Although not all states are that far along, all of them have growing EV markets.

Figure 2: Light-duty EV market share in 2024

Just how much difference does the EV tax credit make when it comes to the economics of vehicle ownership?

Federal EV tax credits take a significant amount off of the purchase price of an EV. However, most of the consumer savings EVs provide are due to the fact that EVs cost less to fuel and maintain, in large part because they are three to five times more efficient than combustion engines. That translates into real savings. The main value of the direct purchase tax credit, in most cases across the Southwest, is to point people towards those savings.

When it comes to vehicles, most consumers are driven by the up-front price that they see at dealerships, making gas vehicles seem cost-effective in the short term despite their expensive downstream maintenance and fuel costs. This is where the value of the EV tax credit comes into play, bringing the purchasing price into orbit for many families who would otherwise be either unable or unwilling to justify spending more on a new vehicle.

To take a closer look at how this plays out for typical drivers across the Southwest, we used Atlas Public Policy’s Dashboard for Rapid Vehicle Electrification (DRVE) tool to compare the total lifetime cost of similarly-sized electric and gas vehicles. We used state-specific data on fuel prices, annual vehicle miles traveled for an average driver, state-level incentives and registration costs, to investigate the effect of direct federal EV tax credits on potential savings opportunities.

(Savings additionally depends on the price of electricity a driver pays while charging. This varies by utility, but typically maximum savings come from charging a vehicle at home or at a place of business at a time of low electricity demand and/or surplus electricity supply – often overnight and into morning hours. To explore this aspect of savings in more detail, see our EV fuel savings tool. Drivers that do not have access to home or depot charging will pay higher fuel costs at public stations.)

With the federal EV tax credit in place, we found that drivers in the Southwest can save as much as $30,000 over a vehicle’s lifetime by going electric. Long term fuel savings and cheaper maintenance tend to outweigh any up-front price premium, registration fees or other extra costs that EVs may incur. EV leases similarly offer savings advantages for individual drivers (although the residual value of an EV after a lease can be a significant point of uncertainty for fleets, given the relatively early state of the resale market).

For example, with current incentives:

- A Reno family that switches to an electric large SUV could save $30,000 (in net present value terms) over a 21-year/200,000 mile vehicle lifetime. That averages out to $1,400 per year, or 23% less than a comparable combustion vehicle.

- If a Tucson driver traded in their gas sedan for a new electric model, they could expect to save almost $11,000 (net present value) over 200,000 miles. That works out to about $500 per year, or 13% overall savings.

- A Denver commuter with a two year lease on an EV sedan could pay under $20 a month, saving over $300 a month when compared to leasing a gas sedan.

With the federal tax credit intact, fully EVs beat out combustion engine vehicles in lifetime costs across every Southwest state and every vehicle type. Due to superior fuel efficiency and comparable upfront costs, larger vehicles like electric pickup trucks and SUVs tend to offer the greatest savings; while smaller vehicles tend to be the most affordable overall.

Pickup truck drivers have the greatest opportunity to save money over the life of the vehicle, saving $28,000 on average (net present value) just from choosing an electric model. That’s equivalent to an extra $120 a month. (See Figure 3 for a comparison of typical cost savings by vehicle type. Figure 4 shows the full total cost of ownership estimates for both combustion and electric vehicles of four general types.)

Figure 3: Typical lifetime EV ownership wavings in the U.S. Southwest, with the federal EV tax credit in place (net present value)

The bars represent the range of available savings across six U.S. Southwest states for four different representative kinds of vehicles, comparing electric models that are eligible for the full federal EV purchase tax credit with similar combustion versions, over 200,000 miles. Wyoming offers the lowest savings. Nevada offers the highest. The “average” bar represents the average across the states, weighted by the size of each states’ light-duty vehicle market in 2024.

Figure 4: Total cost of ownership values for representative vehicles in the U.S. Southwest (net present value)

The bars represent the total net present value of the cost of ownership for four different representative kinds of vehicles, both combustion and electric (fully tax credit eligible), averaged across six southwest states, weighted by the size of each states’ light duty vehicle market in 2024. Sedans tend to be the most affordable overall, while the difference between electric and combustion models tends to be greatest for pickups.

Drivers in Nevada generally have the greatest access to cost savings, in large part because NV Energy offers very attractive discounted off-peak electricity rates covering a large portion of the state’s population, while gasoline and diesel prices in Nevada tend to be higher than in many other parts of the region. Optimally fueling an EV in Nevada is comparable to paying less than 70 cents per gallon of gasoline, compared to $3.75 per gallon at the pump (as of March 2024). This outweighs the fact that Nevada does not currently offer any state-level purchase incentives for EVs – making Nevada even more attractive for EV drivers than Colorado, which has a suite of state-level policies and marketing efforts driving EV deployment.

On the other side of the scale, savings tend to be the least available in Wyoming. The difference between electric fuel and gasoline costs tends to be smaller there. For example, in Cheyenne, Black Hills Energy does not offer a discounted residential time-of-use or off-peak EV charging rate; and gasoline has recently held steady at about $3 per gallon. Additionally, the state charges a $200 annual fee to register an EV and offers no state-level purchase incentives. (However, the economics for depot-based fleet EVs in Wyoming, which could use cheaper commercial electricity rates, are likely much better.)

For vehicles that do not meet the North American assembly or battery sourcing requirements, some dealers are passing along at least a portion of the commercial EV tax credit by offering discounted leases. If a dealer passes on the full $7,500 credit, that would translate to about $200 savings per month over a three-year lease. This has increased the popularity of leasing, with just under half of EV drivers choosing to lease. After the initial leasing period, vehicles could either be acquired by the original lessee, or enter the used market (with the federal used EV tax credit making these vehicles – and the savings they provide – more available to people lower on the income ladder.

Are federal EV tax credits worth it?

Households across the Western states spend nearly 20% of their post-tax income on transportation, the highest expenditure behind housing. Reducing those costs can make a real difference in family budgets. And when people save money by choosing to drive electric, they can invest extra dollars into other priorities. That can produce net economic benefits that ripple across communities.

Analysts predict that, across the U.S., EV tax credits:

- Could help create as many as 750,000 jobs in the battery supply chain by 2040, with at least $40 billion in wages and more than $100 billion in increased gross domestic product;

- Will accelerate economies of scale in EV manufacturing, which could reduce the up-front cost of an individual EV by $3,400 to $9,050 by 2032 – and hasten the point where the up-front cost of an EV will no longer be a serious barrier to expanded market penetration; and

- Insulate the economy from oil price volatility, mitigating the risk of economy-wide recessions.

Efficiency investments regularly produce savings that exceed the value of the initial investment, and that is the case for the federal EV tax credit. For example, the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy estimated that an early draft of the IRA’s EV tax credit would produce a net savings of $12 billion over a decade and create more than 220,000 net jobs (defined as one year’s worth of work for one person). Similarly, a recent macroeconomic analysis put the net benefit of the federal EV tax credit at $1.87 per dollar of spending.

Analysts predict that overall, transportation electrification, coupled with progress in cleaning up electricity generation, would save consumers $2.7 trillion by 2050 (or about $1,000 per household per year over the next 30 years); while preventing 150,000 premature deaths due to air pollution and avoiding $1.3 trillion in environmental and health costs.

Federal EV tax credits are intended to realize those benefits while encouraging a meaningful portion of the underlying economic development to happen within the United States. Federal law currently phases out direct EV purchase credits in 2032 – a slingshot into a future where EVs cost less, up-front and overall, compared to less-efficient combustion alternatives.

What happens without the EV tax credit?

Eliminating the federal EV tax credit would increase the effective up-front price or the monthly leasing cost for a new EV, and make used EVs harder to afford. While the overall cost advantage for EVs over combustion technology would remain intact, analysts expect that EV sales would substantially decrease if they became more expensive to purchase.

Let’s take a closer look at current (2025) overall EV cost savings without the federal purchase credit for light-duty, non-commercial EVs. Figure 5 shows total cost of ownership savings for EVs vs. comparable combustion vehicles in the Southwest, without any direct federal purchase support. Figure 5 shows the range of net savings available through electrification in the Southwest, with the minimum values representing Wyoming; the maximum values representing Nevada; and the average values covering the whole region, weighted by the size of each states’ light-duty vehicle market.

Figure 5: Typical lifetime EV ownership savings in the U.S. Southwest, without any federal EV purchase support (net present value)

This figure includes the same analysis as Figure 3, but without any direct federal EV tax credits.

In every case – with the sole exception of a typical EV sedan in Wyoming – EVs would remain the smarter purchase choice in terms of consumer savings across every vehicle type, across every Southwest state. For example, in Nevada, instead of offering a 28% total cost of ownership savings over 200,000 miles, a crossover would yield 21% net savings. And in Arizona or Colorado, an EV sedan purchased in 2025 would cost about 4% less than a combustion alternative over the full vehicle lifetime (instead of a 13% discount with the tax credit in place). Note also that this analysis reflects current conditions in 2025. In a future where EVs cost less – and combustion vehicles cost more (a function of the fact that EV manufacturers have not yet captured economies of scale or technological advancements to the same degree that combustion vehicle manufacturers have) – the picture will look even more favorable for electrification.

Figure 6 shows absolute vehicle costs in the Southwest without the federal EV tax credit, averaged across the region, weighted by states’ light-duty vehicle market size.

Figure 6: Total cost of ownership values for representative vehicles in the U.S. Southwest, without federal EV purchase support (net present value)

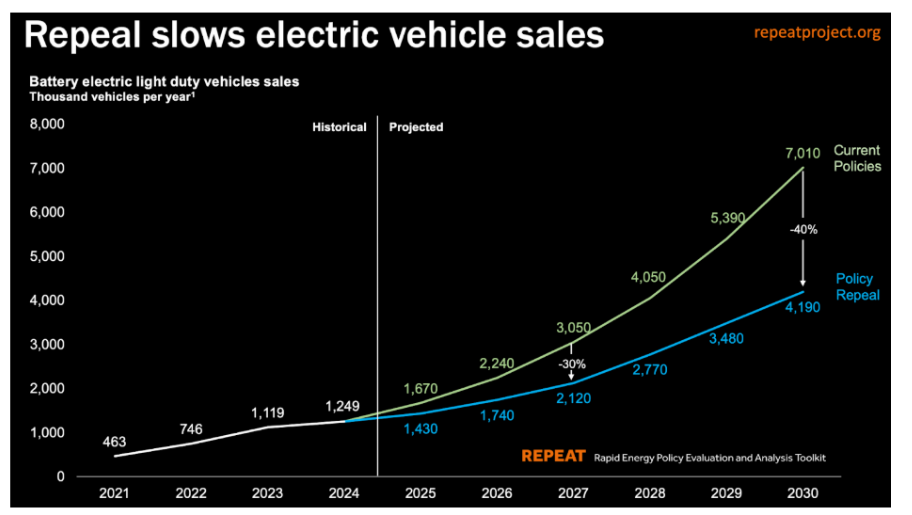

Despite the fact that EVs generally offer savings over their lifetimes – and despite that advantage projected to increase in future years – analysts predict that increasing the purchase price of an EV (by repealing federal EV tax credits) would significantly slow EV deployment, reduce the pace at which manufacturers capture economies of scale, and delay projected benefits.

For example, the Princeton REPEAT project projects that nationally, EV sales could drop by 40% in 2030 without current federal EV incentives. (See Figure 7.) Further, REPEAT analysts project that as much as every single planned EV assembly plant – and half of existing capacity – could be at risk of cancellation or closure. On top of that, “between 29% and 72% of battery cell manufacturing capacity currently operating or online by the end of 2025 would also be unnecessary to meet automotive demand and could be at risk of closure, in addition to 100% of other planned facilities.” That would have dramatically negative impacts on Southwest communities that are gearing up to supply batteries or vehicles to meet currently projected demand.

Figure 7: Repealing federal EV tax credits would dramatically slow EV sales

Source: Analysis by the REPEAT project

In the Southwest, that would translate to tens of thousands of lost jobs; and countless billions of dollars wasted on fuel because consumers bought an inefficient vehicle, thinking they couldn’t afford the more efficient option.

—————————————————-

Methodology

Researchers at the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project (SWEEP) calculated potential vehicle lifetime savings for EVs using local driving patterns, prior research into gas and residential electricity rates, federal fuel economy data, and Atlas Public Policy’s DRVE tool. We attempted to be as regionally-specific as possible, relying on Southwest vehicle usage, county fuel cost, and state incentives and fees for EV registration. However in some cases, namely insurance prices and loan interest rates, there was not sufficient public data available to aggregate generalizable estimates by state, so we defaulted to DRVE’s assumed rate ($600 per year for light-duty vehicles, $4,000 per year for medium-duty vehicles and 7.00% APR respectively). Hence, one’s actual savings may skew higher or lower depending on current insurance rates and credit health.

DRVE inputs and data sources

1) Fuel prices and driving demographic behavior data

The basis of our statewide fuel costs and driving behavior assumptions was derived from our previous research into county-specific residential electricity costs and annual vehicle miles traveled (VMT) data, for SWEEP’s EV Savings Tool.

Typical county VMT data was available through the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s Housing and Transportation Affordability Index, which compiles U.S. Census information. Average statewide VMT, weighed by county population, were then calculated and used in the DRVE input. Hence, annual VMT tended to skew lower than what may be typical in rural areas in which individuals need to drive longer distances to get to places (increasing maintenance and fuel prices, especially for gas vehicles).

Vehicle lifetime use was calculated by dividing the assumed vehicle lifetime VMT (200,000 miles max standard) by the state VMT average. It is important to note that contemporary commercial EVs are believed to be able have the same if not longer lifespans than their gas counterparts under the right charging and maintenance conditions, meaning that our comparison is likely a conservative estimate of lifetime EV savings.

SWEEP researchers compiled the best available residential electricity rate for public, cooperative and municipally-owned utilities across the U.S. Southwest. We identified utilities using bundled residential utilities retail sales data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. For each utility, we looked up residential rate information, and identified the best available rate for EV charging – whether a specific EV rate, a whole-house time-of-use rate, or a generic residential rate. For time-varying rates with seasonal variations, we annualized the rate assuming that the amount of charging would be the same every month year round. Statewide residential rates were then calculated using weighted averages based on county population data from the Housing and Transportation Affordability Index, the same source as the driving behavior data we relied on previously. In DRVE we followed a scenario in which 100% of charging takes place under the statewide average residential rate, assuming optimal charging behavior for our EV cost of ownership analysis.

We took a snapshot of statewide gasoline prices from the AAA Fuel Price Index on February 11th, 2025. DRVE uses information from the U.S. Energy Information Administration to calculate estimated fuel inflation during the vehicle’s lifetime. Regional gas prices may differ, with higher prices increasing the net EV savings and vice versa.

2) Fuel economy data

Fuel economy data for both EVs and combustion engine vehicles was obtained from the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Agency’s Find A Car vehicle catalogue. Both city and highway fuel economy data was used, with DRVE assuming a CC/HW ratio of city to highway driving

3) Vehicle selections

When selecting vehicles for cost of ownership comparisons, we identified highly comparable EV and gas models of a similar type (sedan. SUV, pickup truck, truck SUV), whether the vehicle was eligible for the federal tax credit, the MSRP, and the vehicle’s popularity. We relied on DRVE’s gas vehicle fleet data when identifying gas vehicles to compare with our EV selections, unless there was a case in which there was a more appropriate gas model available. For example, rather than compare the Ford F-150 Lighting Pro pickup truck to the Chevrolet Silverado, as DRVE auto-selected, it made more sense to compare it to a gasoline powered Ford F-150. The make an model for the total cost of ownership calculations are as follows:

- 2024 Toyota Corolla (gas sedan)

- Tesla Model 3 RWD (electric sedan)

- Ford Explorer RWD (gas SUV)

- Honda Prologue EX FWD (electric SUV)

- Ford F-150 2WD (gas pickup)

- Ford F-150 Lightning Pro (electric pickup)

- Jeep Wagoneer 2WD (gas truck SUV)

- Jeep Wagoneer S (electric truck SUV)

Since the state of Colorado has additional EV tax incentives for the purchase or leasing of vehicles under $35,000 MSRP, regardless of meeting the domestic manufacturing and mineral sourcing requirements for the federal EV tax credit, SWEEP decided to analyze additional EVs with more affordable purchase prices. The vehicles under $35,000 MSRP chosen are as follows:

- Chevrolet Bolt EV ($26,595 MSRP, qualifies for federal and state credits)

- Chevrolet Equinox EV ($34,995 MSRP, qualifies for federal and state credits)

- Nissan LEAF S ($29,280 MSRP, qualifies for state credits)

- Hyundai Kona Electric ($34,270 MSRP, qualifies for federal and state credits)

We relied on MSRP information from Car and Driver’s pricing index, and selected the cheapest available EV and gas vehicle to compare. DRVE includes a standard 2.0% annual inflation rate (based on the Federal Reserve’s inflation target), which impacts maintenance and operating costs over time.

4) Fuel economy data

Fuel economy data for both EVs and combustion engine vehicles was obtained from the Find A Car vehicle catalogue. Both city and highway fuel economy data was used, with DRVE assuming a CC/HW ratio of city to highway driving.

5) Purchasing and leasing assumptions

MSRPs were sourced from Car and Driver’s Pricing Index, which are derived from the manufacturer. Given that loan rates and procurement varies so much between individual consumers, we did not think that it would be feasible to analyze every potential procurement option, and instead we relied on DRVE’s purchasing assumptions, which assumes upfront full-price cash purchases. Thus real savings may differ slightly, however given that EV and gas vehicle loans operate the same, there’s likely to be significant differences in savings beyond residual interest.

Leasing information was provided from multiple local dealerships, confirming that the federal EV tax credit was directly applied to negotiating residual value for each individual lease term at the time of financing. While DRVE does have a lease function, similar to the customization issue with identifying differences in loan costs, we assumed leasing cost-savings based on qualifying tax credits to be the best generalization of savings.