May 16, 2023 | Rachel Ellis

Gunnison County, located in central and southwestern Colorado, ditched the furnaces for heat pumps when constructing and remodeling five of their county buildings. In the past few years, county leaders have both identified existing buildings that could operate on heat pump technology, and imagined and constructed brand new buildings that could do the same. Now, one of their oldest buildings in town is more comfortable with a heat pump system for space heating, and their regional airport terminal will be net-zero energy for its heating needs. Additionally, the county upgraded their Health and Human Services building and built a brand new, all-electric courthouse and library.

Choosing geothermal

The county quickly understood the possibilities and potential of using geothermal combined with a distributed heat pump system. They were really excited about how that enables them to move energy within their buildings to balance comfort needs and the ability to treat different spaces with varying strategies for ventilation and conditioning to maximize both comfort and efficiency. “I used to cringe when I would see a building running both its central heating system and cooling system at the same time in order to meet variable loads in the building,” explained John Cattles, Assistant County Manager of Operations & Sustainability.

Now when those mixed conditions arise, the county can see how they can move energy to where it is needed in their buildings. “We also used to have to ventilate empty rooms based on a time-clock occupancy schedule, now we can sense occupancy using CO2 sensors and ventilate as needed. These are just a couple of the energy and comfort advantages to a distributed geothermal heat pump system.” Cattles said.

On their first geothermal heat pump project, the county focused on energy use and cost. Once they realized how efficient heat pumps are and how nicely a heat pump based system works to maximize comfort it was an obvious decision. On the first project, they still included a gas boiler as backup but never needed it. When they began planning their next projects, they wanted to design a system to be sustainable with no need for gas backup. They found that eliminating a gas backup ended up saving them money and made the system much less complex with less control points necessary to manage the system. Since then, Gunnison County has committed to not including gas and relying completely on the electric heat pumps with the geothermal well field. “All electric buildings align well with the County’s values and commitment to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. We can drastically reduce emissions from our own facilities while maintaining high levels of quality and comfort,” Cattles said.

Once the county decided to forego fossil fuels and transition to all-electric buildings, a geothermal system proved to be the best option. Geothermal systems, also called ground-source heat pumps, exchange energy from underground and transfer that energy through a water distribution system to equipment in each building, zone, or room where a heat pump ether mines energy from the water loop or rejects energy to it depending on if it is heating or cooling the space. Gunnison County often faces harsh and variable weather conditions, with winter temperatures falling below -30° F, so the constant temperatures underground is more efficient and cost-effective than another popular all-electric option — pulling heat from the ambient air using an air source heat pump.

The size of the system also led to the choice for geothermal. “Very few air source heat pumps were practical for the size of the buildings, but ground source heat pumps could be networked together to fit what we needed.” he said.

Finally, the amount of refrigerants played into the decision to go with geothermal. “As opposed to commercial-scale air source heat pumps, which have to run long lines of refrigerant throughout the building, our system uses water for the heat transfer so there is less risk of leaking and losing refrigerant to the atmosphere. When thinking about climate and environment on a large scale, these are the decisions that matter,” explained Cattles.

Funding for the five buildings

The county put together a workable package of funding from a combination of sources.

- Energy performance contracts. The Blackstock project was funded through an energy performance contract, which uses the project’s ongoing savings to gradually pay for the upfront costs. The Colorado Energy Office has assisted local governments with learning about and setting up performance contracts, offering contract and procurement templates, so the county doesn’t have as much of a learning curve. “They also have engineers that vet the proposals to review the performance and finance pieces,” said Cattles. “The performance contract locked in a long-term price for us, and that shielded us from the market. From a fiscal standpoint, we like the assurance and low risk. Using financing to create future cost security is maybe not the most popular approach, but it’s an effective one.”

- Lease-purchase agreements. Lease purchase agreements or Certificates of Participation are a finance mechanism available to local governments that have been used to finance improvements at Blackstock and the Courthouse.

- Cash on hand. The county commissioners decided that durable, resilient, low-carbon buildings would serve the community’s long-term interest, and were willing to use some of the annual budgets towards these goals.

- Tax-payer approved funding. Gunnison County residents voted in 2019 on how their tax dollars could be spent for a new library building on donated acres of land, and the results came back with strong public support to make the building all-electric. That tax funding, combined with a $1 million endowment from the rancher who donated the land, became the main source of funding for the library project.

- State grant funding. Colorado’s Department of Local Affairs (DOLA) has a grant fund for local government and community projects, stemming from sales taxes from energy extraction companies. “Severance tax receipts, some of which are from oil and gas extraction, helped pay for us to get off of natural gas, which I think is pretty cool,” said Cattles. The DOLA grant cycle is typically twice a year, and Cattles says it’s an easy application that, when awarded, helps to cover the gap between organic cash flow and energy performance contracts. “It’s a state agency with a mission to support local governments,” Cattles said.

- CARE Act. The Gunnison/Crested Butte Regional Airport received CARE Act funds in 2020 which helped close the funding gap for the project and allowed us to maintain high standards for energy efficiency and occupant comfort in the building.

- Economies of scale. The county packaged together estimates for installations for multiple different buildings into one package, which made the solar pricing more affordable.

Retraining local engineers and architects

One of the main challenges the county faced was getting engineers and architects to think about HVAC in a way that is new. “Having the values was easy — it was the implementation that was hard.” Cattles said.

For example, instead of accepting building plans based on old fossil fuel-based systems, Cattles and his team had to actively help conjure up plans that took advantage of the capabilities of geothermal and avoid trying to force geothermal into heating and cooling strategies that were developed for gas systems such as centralized heating systems. Ground source heating systems have their own strengths and weaknesses and require a different strategy than traditional systems to take advantage of the strengths and minimize weaknesses.

Gunnison County has used a variety of contractors to install their geothermal systems over the years. Recent projects have been installed by local contractors which is a huge advantage for being in a remote area of the state. Their local contractor has been able to train workers and adapt to heat pump HVAC systems with remarkable speed. These systems are different but their experience has proved that well qualified HVAC technicians are able to adapt without much trouble or expense.

Overcoming the initial resistance helped lower their overall costs and eliminate the need for gas backups. “Everytime there’s a new engineer, there’s another learning curve,” Cattles said. “But we’ve been able to replicate results because so many people are involved in the process and the County is committed to following through with projects that match our values. Buying into a new HVAC strategy works.”

Guaranteeing results

Cattles said that, as a non-expert, finding a way to ask the right questions was key. “We needed to probe until we could get apples-to-apples forecasts and comparisons from engineers and architects.”

“Use your goals to guide the project, especially regarding energy use. We made performance part of the contract to ensure accountability that those performance standards would be met,” he said. The county accomplished this by setting Energy Use Intensity (EUI) goals, which specify a maximum amount of energy used per square foot once the building is fully up and running.

In working the numbers, the ideas, and the parameters, the county was able to lower their costs and meet their goals with ease. “Government buildings always remain part of the infrastructure of a county, so it makes sense to do these projects that have a long life because they’re not going anywhere.”

Blackstock government building

Quick facts

- Size: 26,200 sq. ft

- Date of construction: 1926

- Date of retrofit: 2021

- Cost: $1.7 million

- Heating and cooling: Geothermal

- EUI: Reduced from 91 to 27 BTU’s/sq.ft./yr

- Additional efficiency upgrades: 32 kW solar system providing 30 percent of building energy supply

- Total energy reduction: 72 percent (solar + heat pumps)

The Blackstock building in Gunnison, Colorado has served as a local government administration and community space since its construction in 1926.

The building was originally heated using steam from a coal fired boiler. The last renovation to the building was in 1999 when the county upgraded to boilers and chillers, but gradually those systems experienced multiple failures. Even though all the rest of the components of the building were intact and functional, the staff knew they had to do something to break the high maintenance cycle and upgrade the heating and cooling system to something more efficient. “We got to a place of being okay to retire equipment that still has life in order to move forward with a big renovation,” explained Cattles. “It’s worth the investment for a fundamental switch that we knew would result in long-term, reliable equipment. And it aligns with our commissioners’ values for climate.” Based on the efficiency, the long-term cost savings, and the zero emissions, the county chose a geothermal system, shared with its nearby Health and Human Services building.

The new system captures heat from underground and circulates it throughout the building in a water distribution system. There are 19 water-to-air heat pumps and two water-to-water heat pumps. They are zoned based on the orientation of the sun, creating an equilibrium that helps the building’s efficiency to skyrocket. Radiant baseboard heat spreads throughout the building, and the entryway has hydraulic heaters with fans to keep that space comfortable when the doors open throughout the day. The radiant baseboard heat keeps the building warm when vacant, and the heat pumps kick on when the building is occupied. In a nod to the building’s past, the engineers were able to retain some remnants from its original steam system, repurposed and adapted to the new system.

“Before the transition, the upstairs would get sweltering hot. With the new geothermal system, the air is even, warm, and comfortable in the summer and winter,” said Cathie Pagano, Assistant County Manager for Community and Economic Development in Gunnison County. “To come and work in a building this old and that’s still comfortable is amazing. A lot of the staff went to elementary school here, so it’s nice that something that is part of our community is well-taken care of.”

Health and Human Services building

Quick facts

- Size: 11,600 sq. ft

- Date of construction: 1952

- Date of retrofit: 2017

- Cost: $570,000

- Heating and cooling: Geothermal

- EUI: 32 Btu/sq. ft. /year

- Total energy reduction: 66 percent (heat pumps + solar)

- Additional efficiency upgrades: 25 kW solar array

Gunnison’s Health and Human Services building, built in 1952, houses the County’s Human Services, Public Health, and Child Welfare departments. As the building aged, the original heating and cooling system struggled to maintain comfortable temperatures for the staff. Adding insulation wasn’t practical because of the building’s historic construction, so Cattles and his team decided that updating the HVAC was the best strategy for both saving energy and improving comfort. The county had planned to do a complete remodel of the floor plan anyway, further affecting the heating and cooling system’s effectiveness, so that was the impetus for investing in a new system.

The county expanded the geothermal system serving the Blackrock administration building in order to serve the Health and Human Services building as well. The geothermal system transfers the steady underground temperatures through water pipes throughout the building, ending up in 10 water-to air-heat pumps. A solar array came about two years after that.

Gunnison County Courthouse

Quick facts

- Size: 45,886 sq. ft

- Date of construction: 2016

- Cost: $2 million

- Heating and cooling: Climate Master

- EUI (Btu/sq. ft./year): 31

The newly-constructed Gunnison County Courthouse was the county’s first building to try all-electric geothermal heat pumps, and the success of the project led the county to use geothermal in the other county buildings as well.

The courthouse’s geothermal system captures warm temperatures from underground and transfers the heat through water distribution pipes to 64 water-to-air heat pumps, each with its own thermostat. The heat pumps themselves are quite compact — about the size of a mini fridge — and are controlled by zone-specific thermostats.

Compared to the previous traditional HVAC system with gas furnaces and boilers, the building is estimated to reduce energy cost by about 75 percent, and 68 metric tonnes in GHG emissions per year.

Other features of the building include:

- Demand-based ventilation that helps maintain healthy and fresh air and keeps carbon dioxide concentrations minimal.

- A tight building envelope that can uphold 72-hour survivability standards, via R-20 fiberglass insulation in the interior and R-16 insulation on the exterior, for an overall R-35.

- Heated concrete floors as well as a heated handicap ramp outside. These currently use gas, but the county aims to remove the gas backup and gas elements of the building sometime in 2023 since it’s the only thing keeping the building from 100 percent electric.

- Solar, added in 2020.

The system has already proved its worth on numerous occasions. When the county experienced a 48-hour power outage, the building retained a temperature of 50° F even when outside temperatures were falling below 0° F at night.

Using multiple heat pumps in the building added extra reliability. “One heat pump out of 64 failed recently because of a control issue, but because we had other units in the area we were able to adjust and provide necessary heating to the space and maintain a comfortable working space, so the distributed nature of the system is what keeps things resilient,” said Cattles.

“This is the most comfortable public building I’ve ever been in,” said Matthew Birnie, Gunnison County Manager. “Our goal with these projects was efficiency, climate, and total life cycle cost. Marginal costs are small relative to the savings because the energy is essentially free.” Birnie added, “The project proves that this technology works, and gives us the confidence to say no to gas.”

Gunnison County Library

Quick facts

- Size: 15,000 sq. ft

- Date of construction: 2022

- Cost: $1.7 million

- Additional items: 25 kW ground-mounted solar array

The Gunnison County Library is a new point of community pride, attracting local residents for meetings and events, studying, and learning. It replaced an older library building, when residents asked for a more functional and flexible community space. The library is one of five county buildings that are all-electric, needing no fossil fuels.

Like the other buildings, the library uses geothermal energy — capturing heat from underground with a ground source heat pump and distributing it throughout the library using a water loop.

In December, the library’s entire energy bill was just $62.45, and in January it was only $73.72.

Gunnison County Airport

Quick facts

Size: 48,000 sq. ft

Date of construction: 1983

Date of retrofit: 2021

Cost: $1.7 million

Heating and cooling: Geothermal

Additional efficiency upgrades: Two hot water heat pumps and radiant heat

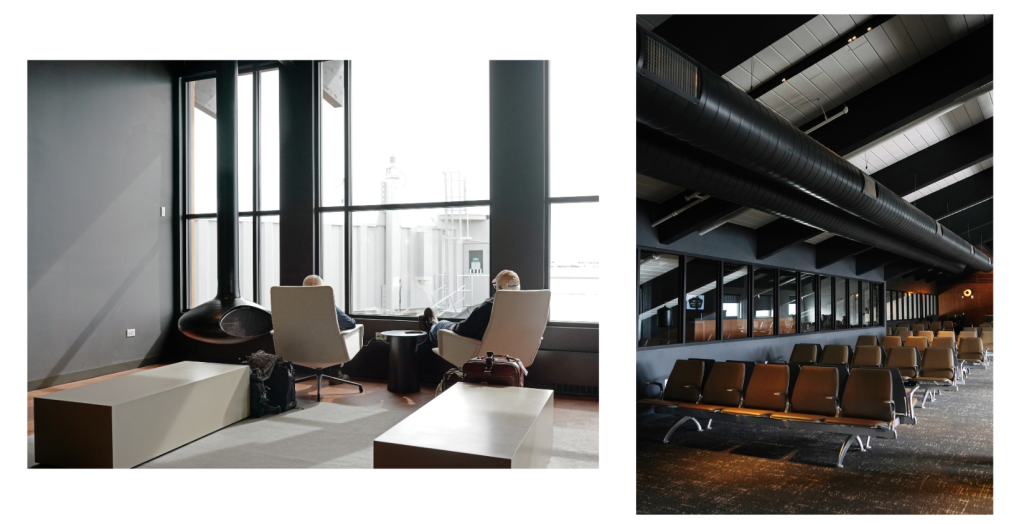

The Gunnison County Airport is a small public airport about a mile south of town, with a terminal building housing four gates, baggage distribution, offices, and rental car counters. It’s the fourth building the county converted to run on highly-efficient geothermal energy, instead of relying on traditional fossil fuel heating.

The building is all-electric, there is no gas service to the building. The system circulates water from a geothermal well-field that is next to the building to air source heat pumps that are distributed throughout the building. The system also includes 2 water to water heat pumps that provide hot water to a radiant baseboard system and hot-water cabinet unit heaters that provide extra heat at entrances. Since the airport is a federal project, the design and concept for the terminal took four years of planning. The county had to work through FAA regulations, obtain approval from Homeland Security and TSA, and meet local building codes, so the process was very bureaucratically intensive.